Teri McFadden is a Principal for Talent & Retention in Norwest’s Portfolio Services team. She has more than 20 years’ experience in leadership recruiting and human resources development. She offers her observations about why, when, and how startups can use retention equity as a compensation tool.

Retaining top talent is an escalating priority for companies of all sizes, but early-stage startups have a narrower range of tools to achieve this goal compared to large, established enterprises. Most startups must be careful about how much money they allocate to salaries, and promotions to more senior positions are limited when total employment is only in the low hundreds. So, equity takes on an outsized role in compensation plans.

Follow-on grants of stock options are sometimes used to retain key employees, but without proper planning and a clear strategy, such “retention equity” can lead to unintended consequences, disgruntled employees, conflicts with the board, and depleted coffers.

That’s why founders of young, private companies must pay close attention to three topics when devising their compensation strategies:

- What is retention equity and how can it become a challenge?

- How can retention equity cause problems with employees and boards?

- What guidelines and best practices should startups follow for effective retention equity?

The Long Road to Exit Leads to Retention Equity

For decades, it has been standard practice in startups to grant employees stock options as a major element of compensation. In most cases those options are fully vested in four years. Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, most companies were exiting in four to five years, which meant employees were able to realize the value of those options fairly quickly. Today, however, we’re seeing companies exit in eight to 10 years, or even longer. So that four-year vesting window doesn’t reach the exit point. That leaves some employees frustrated. When that happens, management can be tempted to sweeten the pot with additional options – or retention equity.

It’s not only an issue with early employees. As companies mature, they start to hire from larger public companies whose employees may be accustomed to receiving RSUs (restricted stock units), which give employees equity on an annual basis but are less costly to the equity pool. These employees may not understand the difference between public company RSUs and private company stock options and are likely to desire a program in which they receive ongoing grants. Hence, more pressure on management to offer retention equity.

I never heard about retention equity when companies were exiting in a few years, but it’s becoming a big issue as the time to exit lengthens. Now, I frequently hear from CEOs of our portfolio companies who are seeking guidance on retention equity.

What I tell them is to think carefully before taking any action, because the perceived short-term benefits may be overwhelmed by longer-term challenges. A young company is naturally focused on a relatively small number of hires, but as a company grows and the number of employees increases, a retention equity program can become quite “expensive” (i.e., dilutive to the option pool). Once the expectation of a retention equity program has been set with employees, it can be damaging to morale to take it away when it does become too expensive, erasing any benefit the program might have had in earlier days. So, I tell even seed-stage companies to think about what their strategy will be for retention, because it’s going to have long-term impacts on their equity pools and burn rates.

Even seed-stage companies must think about what their philosophy is for retention, because it’s going to have long-term impacts on the equity pool and burn rate.

Slicing the Pie Ever Thinner

A helpful way to think about the long-term impact of retention equity is to imagine equity as a freshly baked pie.

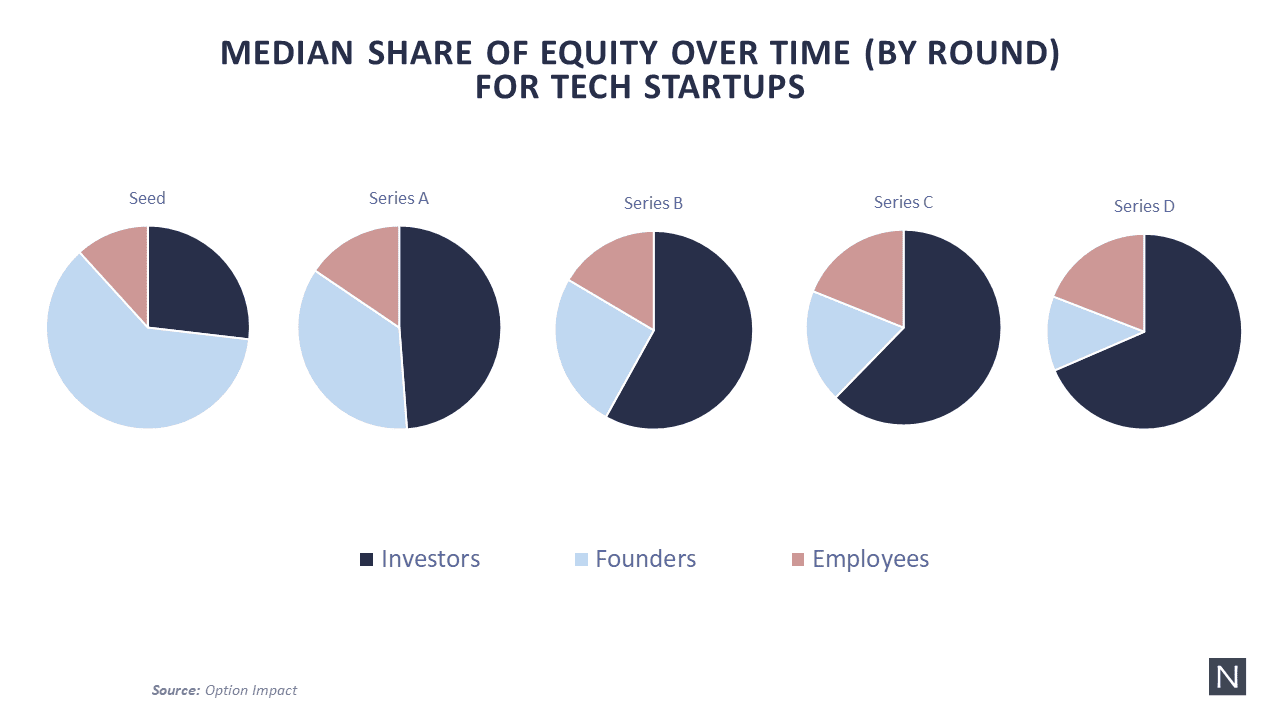

When a company is formed and has its initial funding, there is a pool of equity: founders’ shares, investors’ shares, and employees’ shares. That’s the whole pie. A couple of decades ago, those three segments were roughly equal. Over the last 20 years, as exit windows have lengthened, companies have had to raise more money. When founders raise more money, the investor slice of the pie gets bigger while the founder and employee slices get smaller. As companies add more people, the employee piece of the pie is further divided to accommodate new-hire grants. So, leaders concerned about keeping key employees are working with a slice of pie that is smaller and is divided among more people over a longer period.

Here’s the basic challenge: it’s a finite equity pie with slices for founders, investors, and employees. It’s not like a public company that issues evergreen grants every year and RSUs that don’t have a strike price. It’s a much different environment in a private company, and private companies at all stages need to clearly communicate to employees how options work, what their value is, and how to formulate a wealth-creation plan based on that new-hire grant. The leadership should manage expectations so employees do not assume they will continually get more options over time. Even the semantic difference between “refresh” and “retention” communicates an important distinction.

Pre-public companies must be very judicious about who receives retention equity, because if they set up a program where everybody receives retention grants every one to two years, it consumes too much of the pie. At some point, the board will step in and say they’re not going to support it, and then the leadership has a problem when employees who expect a retention benefit see it taken away.

Pre-public companies must be very judicious about who receives retention equity.

I have seen this in portfolio companies that have had generous and expensive retention equity programs that made annual grants to all employees. That works great for three or four years, but then the board says we’ve got another three to four years to go before we exit, and we can’t continue to fund this program because we need the options for new hires. Then instead of a retention benefit, they have a retention issue with disgruntled employees.

That’s why it’s critically important for management to have a philosophy and strategic approach to the role of equity in employee compensation that is modeled out for the long term. We encourage founders to build their equity compensation plans as early as possible. It may seem premature to do this when you’re still a very small company, but it can save a lot of frustration and challenges later on. We work with our CEOs/founders to build these plans, especially when they don’t yet have a head of Finance or HR.

It’s critically important for management to have a philosophy and strategic approach to the role of equity in employee compensation.

Of equal importance is how leaders communicate the company’s philosophy and strategy to all employees; communication must be clear and consistent.

Retention Equity Alternatives and the Importance of Communication

Managers concerned about keeping a high-value employee have some alternatives. For example, “boxcar vesting” is a technique where the follow-on grant doesn’t start vesting until the new-hire grant is fully vested. However, it can have an accelerated schedule, so that at the end of, say, six years, the employee has both their new-hire and retention grants fully vested. So you can issue retention equity at an earlier time frame (when someone is only 50% vested) at a lower strike price instead of waiting until they are fully vested and the strike price is likely higher.

One program we offer to our portfolio companies is manager training around compensation: taking them from seed stage through exit and showing what happens to equity in that process, and how to communicate that to new hires.

For later stage companies, it may make sense to switch the focus from percentage ownership to the value of equity when communicating to employees. For many employees, equity is a mysterious black box that someday might contain a lot of money, but they don’t really understand how it works. So, I encourage companies to give employees a simple spreadsheet where they can do their own math. If they’re evaluating opportunities at other companies – and if compensation is a big factor in their decision – they should be able to calculate the potential value of X number of RSUs over the next four years at an established company versus what their new-hire grant might eventually be worth.

I believe companies should educate their employees that wealth creation in a startup comes with the initial hire grant. The focus for every single employee – from founder to individual contributor – should be on creating additional value in that initial grant. They also should know that subsequent grants aren’t going to be as meaningful.

Companies should educate their employees that wealth creation in a startup comes with the initial hire grant.

Two things happen when a company refreshes equity three or four years after someone has joined:

- The amount is significantly less than the new-hire grant

- The strike price (if the company is doing well) is much higher

At exit, then, the initial grant is going to have a lot more value than the retention equity. It’s very important to clearly communicate to employees that when they join, they’re here for the long term. The reward for this commitment is a greater return on their initial grant through a successful exit.

Designing the Optimum Retention Equity Program

I’m not saying retention equity is a bad idea, but it is one that must be carefully designed and explained. Here are some suggestions for setting up a program for success:

- Retention equity plans should be conservative programs that allow for additional equity grants to top-tier employees. Managers should clearly communicate that these are “retention” grants — not “refresh” grants — that are awarded based on performance and are not given as standard practice.

- Retention equity should be calculated using 25 percent of a new-hire grant.

- Plans must balance equity conservation and smart distribution for targeted retention.

- Decide on the eligibility date for employees to receive retention grants (when they are 50 percent, 75 percent, or 100 percent vested in the initial grant); then decide on the vesting schedule (standard four-year vest with or without a one-year cliff; or boxcar vesting). Many companies choose 75 percent vested on new hire grants and standard vesting with a one-year cliff on retention grants, which is relatively conservative and easy to communicate to employees.

- There should be a culture of understanding that the value of the initial equity grant is the primary vehicle for wealth creation.

- Compensation decisions must be based on hard data. Work with a provider like Option Impact, which is probably the best source for venture-backed data, particularly for equity.

- Compensation and equity bands should be determined early in a company’s life, then continually reviewed and adjusted as the company increases in size and revenue and raises additional capital.

The Takeaway

Retention equity can be a valuable tool, but it should be only one element in a larger compensation and retention strategy that takes a long-range view, targets a select number of high-value employees, and is communicated clearly and consistently.

About the Author: Teri McFadden is a Principal for Talent & Retention in Norwest’s Portfolio Services team. She has more than 20 years’ experience in leadership recruiting and human resources development. During her career, Teri has cultivated a robust network of entrepreneurs, executives, and key industry influencers to help grow portfolio companies with the best possible management teams and boards of directors. She works closely with Norwest investment professionals, co-investors, and board members, as well as portfolio company founders and CEOs, to evaluate new investment opportunities and grow existing portfolio companies.