At Norwest, we believe that some of the biggest disruptions of the next generation will occur within our food systems – both in terms of what we eat and how it gets to the plate. Many of these changes have massive potential to expand food access and drive sustainability within this massive industry. Our teams have been actively investing in this space for a while now, across alt-protein (Upside Foods, formerly Memphis Meats), consumer packaged goods (Kishlay Foods, MTN OPS), and food-focused marketplaces (Imperfect Foods, Swiggy).

Our guest, Jo Zhu, a student at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, shares our passion for this future. Jo spent 10 weeks with us focused on the many changes occurring in the space. In this three-part series, she shares how COVID has accelerated a number of key trends, insights on emerging business models, and a breakdown of the core technologies unlocking sustainability levers for the next generation.

This is part 2 of our Future of Food Blog series. You can also explore part 1 here and part 3 here. Part 2 focuses on the evolution of food delivery, ghost kitchens, virtual kitchens, and commissaries.

Introduction

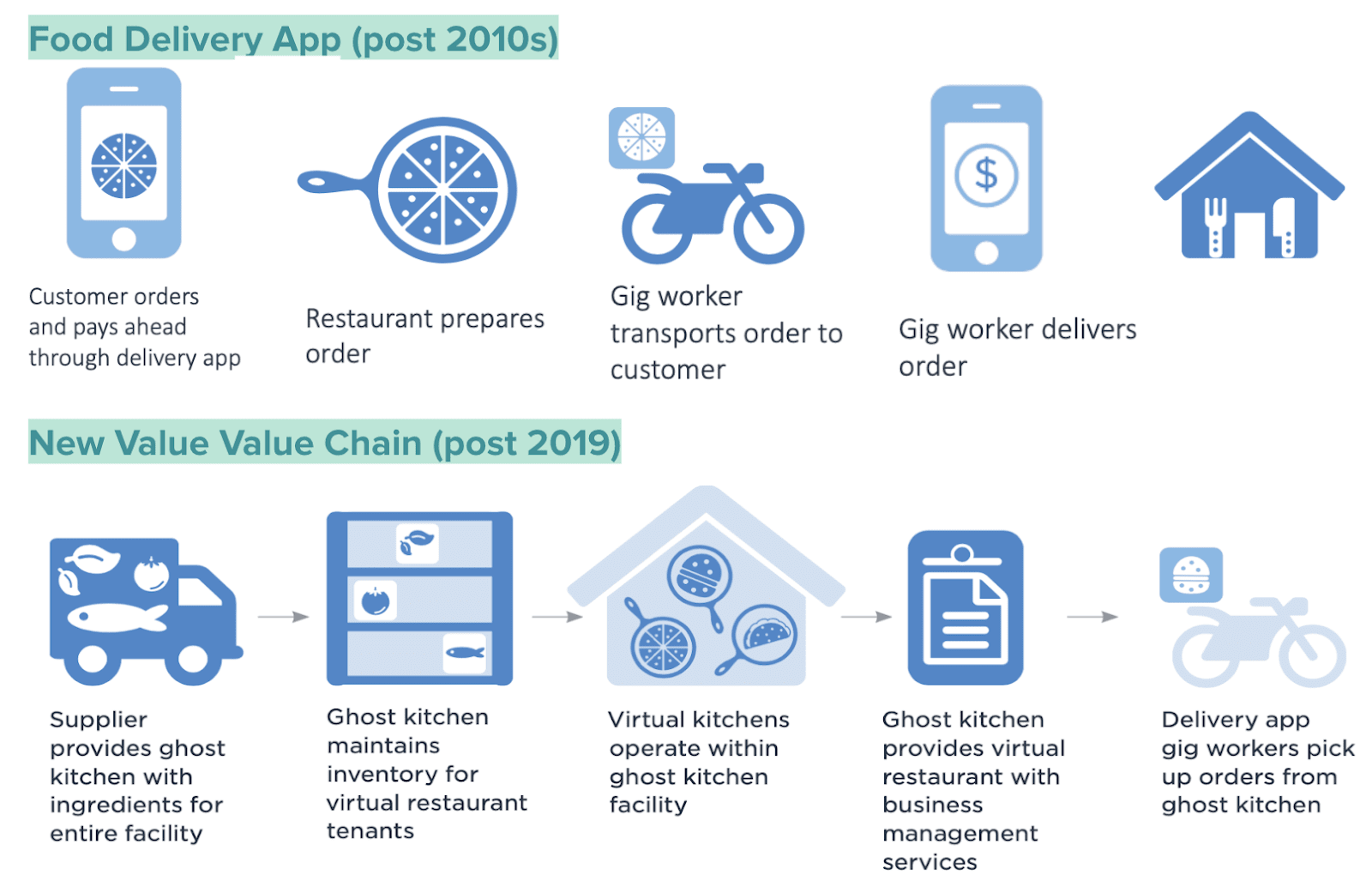

With indoor dining largely shut down, the restaurants that survived—and in some cases thrived—during the pandemic were those able to pivot to digital and off-premise sales methods including takeout and delivery. Prior to digital food ordering apps, relatively few restaurants offered delivery, and customers relied on mailers, door hangers, phonebooks, and other ads to discover new places to eat.

Early food delivery apps, such as Seamless and Grubhub, targeted these inefficiencies by aggregating restaurant menus and contact info into one place. In the early 2010s, food delivery platforms took off as VC-backed startups (most notably DoorDash and UberEats) aggressively attacked the market by providing both demand generation and delivery on behalf of restaurants.

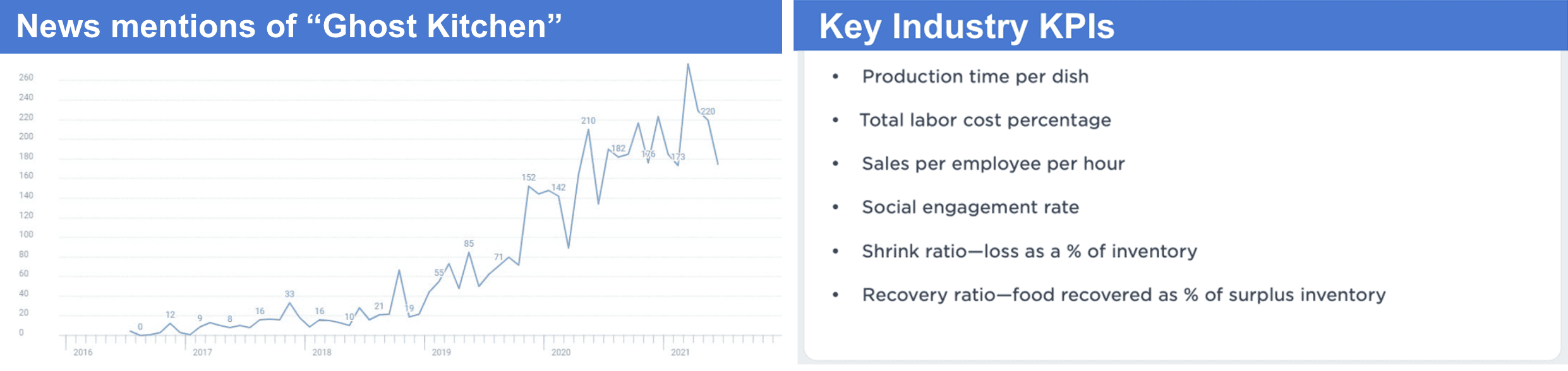

In 2021, both food delivery app providers and VCs are investing in solutions to tackle the issues of labor shortage: the two most invested in areas are reducing transportation costs through autonomous vehicles and reducing the cost of restaurant operations through the use of ghost kitchens.

Ghost kitchens allow food providers to aggregate delivery-focused food production at centralized locations, potentially reducing preparation and delivery costs while generating additional revenue streams from restaurant tenants.

Source: PR NewsWire

At first glance, ghost kitchens appear to be a simple application of WeWork’s office leasing model applied to restaurants. However, the industry reflects trends that are reshaping the business model of “restaurants” as delivery becomes more mainstream. Versions of ghost kitchens have existed for years, including in the form of commercial kitchen spaces which are subdivided and leased to multiple restaurants.

But while these early models were intended more for commercial use, what’s even more interesting are the virtual restaurants that occupy the middle of this supply chain. These startups neither buy property nor operate a fleet of couriers – rather, they lease from the ghost kitchens and pay for white label delivery. This is where the data lives and allows for venture growth multiples that are not sullied by the CapEx intensive nature of ghost kitchens (which in essence are real estate holding companies of commercial warehouses).

Source: RestaurantOwner

Who are some of the players in the ghost kitchen & virtual restaurant space?

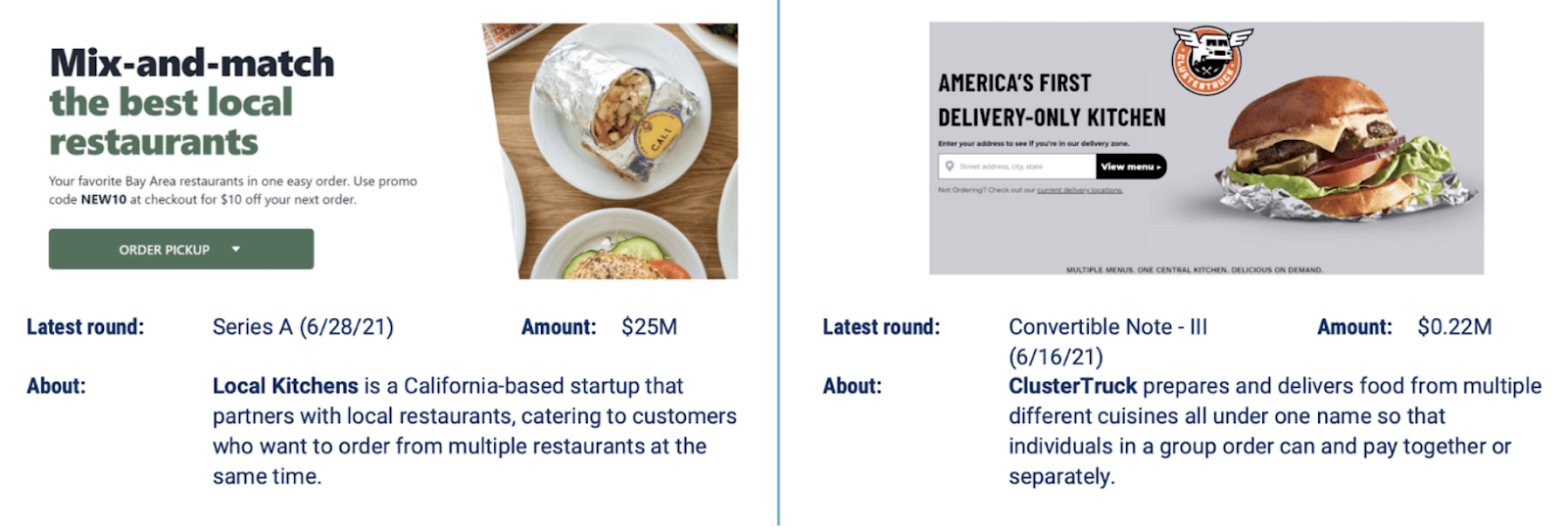

Ghost kitchen facilities are a real estate play – they convert unused warehouses or storefronts that vary in layout and convert them to be optimized kitchens for food delivery only. Some ghost kitchens provide a communal stock room, while others give clients the space to manage their own inventory. The kitchen layout is optimized for delivery, and some facilities provide a variety of business services that allow the client to focus solely on food preparation. The estimate is that there are over 1,280 ghost kitchen facilities globally, primarily located in large, densely packed cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

While ghost kitchens tend to be located outside core commercial areas where real estate is most expensive, some providers are changing that trend. For Local Kitchens and ClusterTruck, both centralize back-of-house tasks such as sanitization and inventory management, as well as front-of-house tasks such as delivery management and catering. Rather than using more industrial locations to minimize real estate costs, these two startups (similar to All Day Kitchens) facilities are located in commercial cores to encourage customer pickup and minimize delivery time.

Virtual restaurants are a branding play – they are creating consumer food brands (think MonsterMac) that eaters can order on food marketplaces (like DoorDash) or their own first-party website like Foodology, which exists only in delivery mode. Most of these startups are taking the point-of-view that solving food automation requires leaning into special-purpose hardware, rather than just trying to program a robotic arm to do everything a human cook does. We chatted with a few AI researchers, and the insight is that there are tremendous difficulties in programming arms to do even simple tasks like pick-and-place, let alone cook full meals. And if you’re going to constrain the kitchen environment to help the arm’s actions be more repeatable, you might as well use special-purpose hardware that can do the same tasks more quickly and reliably.

What’s the trend driving the growth in ghost kitchens and virtual restaurant brands?

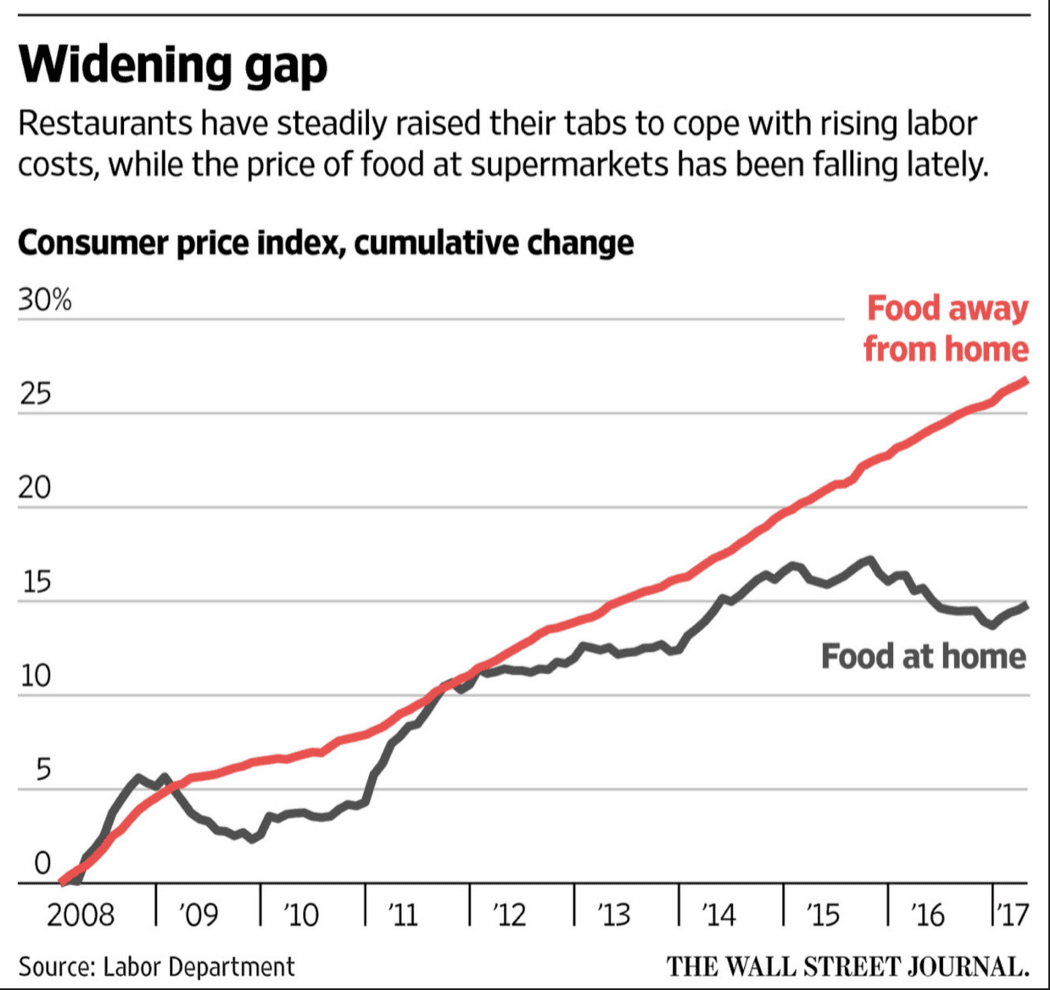

- Eating out is outpacing eating in

- More and more, Americans would rather eat food that’s prepared for them than buy groceries to cook at home. That, paired with the fact that in the last decade, the average size of new apartments in the US—kitchens included—has decreased by 9.7%. This trend of shrinking kitchens reflects US consumers’ ebbing interest in gourmet cooking and concurrent heightened dependence on restaurant dining, food delivery, and prepackaged meals as their primary food sources.

Source: Northwestern Business Review

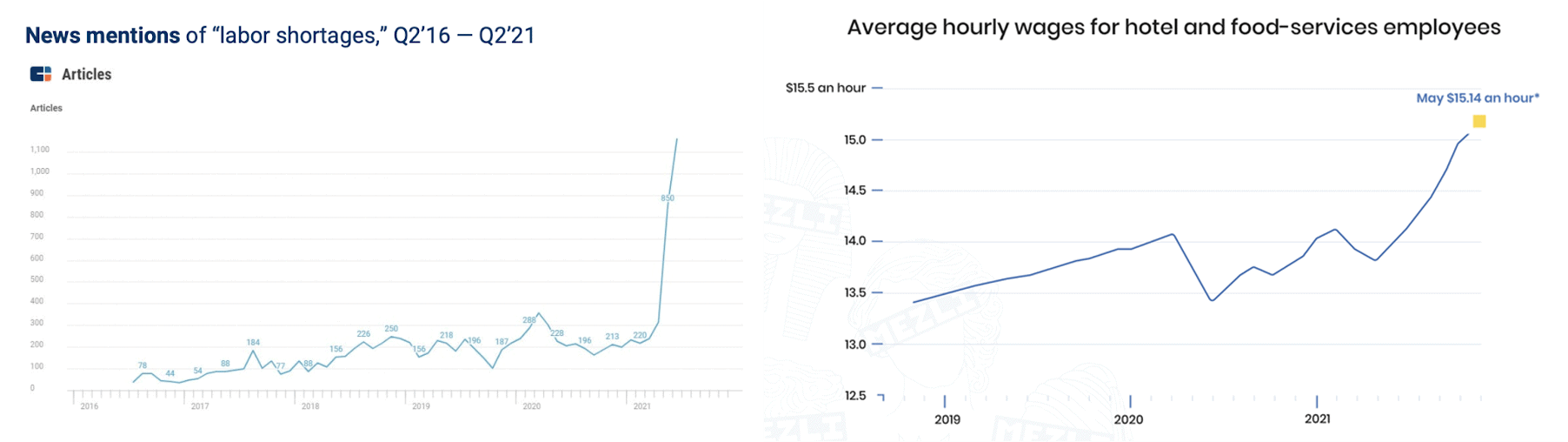

- Labor shortage

- Restaurants are struggling to hire enough labor to meet demand and that labor is growing more expensive. The Covid-19 pandemic has had lasting effects on the food industry, from production to supply chain to delivery. Labor shortages are one of the biggest issues the industry faces, as restaurants struggle to replace workers laid off during the pandemic. Restaurants like McDonald’s and Chipotle are raising wages and offering bonuses to attract more workers.

Source: Labor Dept

Mobile Commissaries will be on the rise as well

Imagine a piping hot coffee or pizza delivered to your office or home at the proverbial “click of a button.” For consumers, it’s perfect. For the startups attempting to provide these services, it’s a bit more complicated. But what are the post-COVID macro trends that are driving the rise of mobile commissaries?

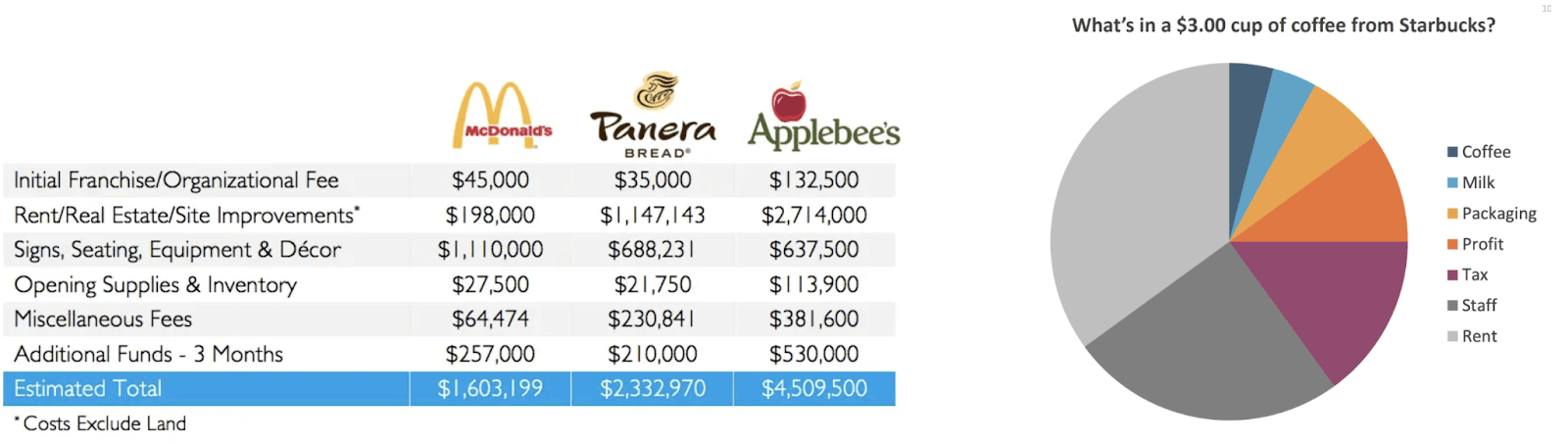

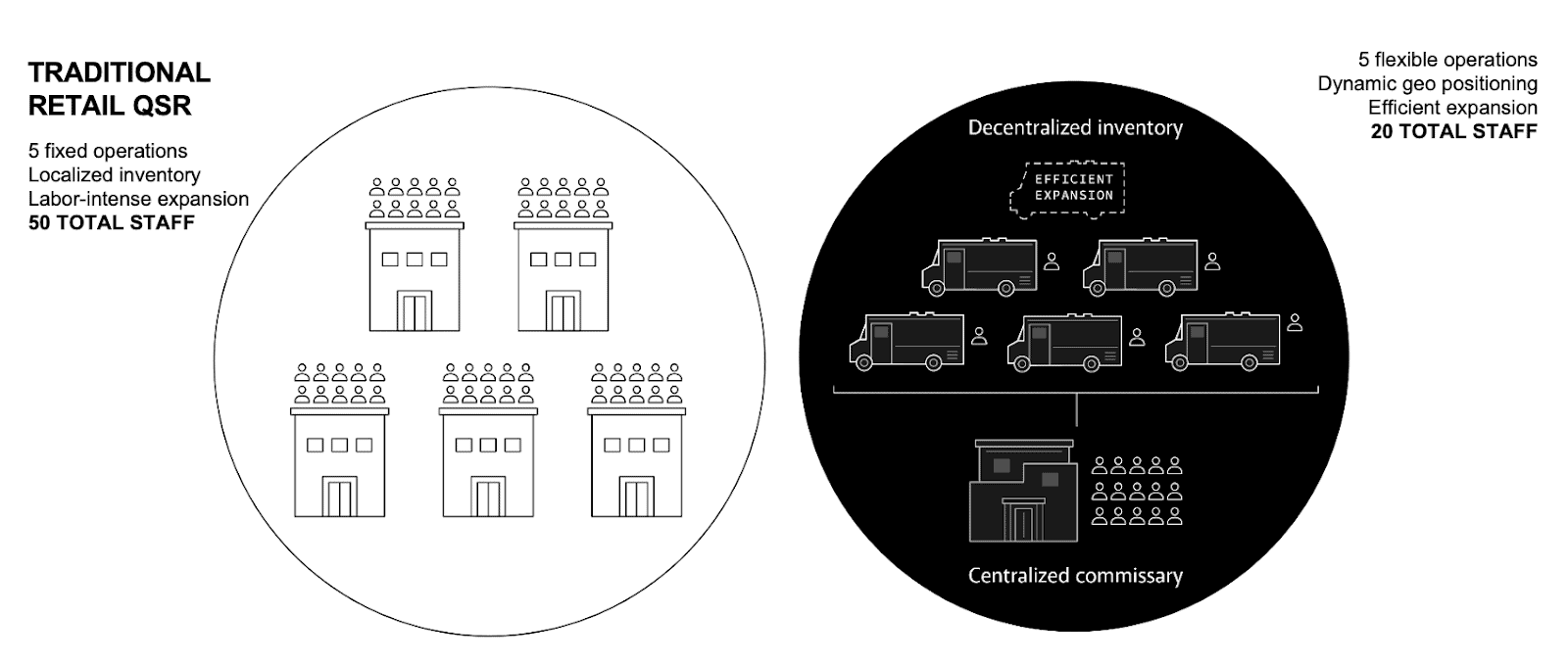

- Reduce labor and real estate

- A mobile commissary’s main advantage over traditional brick and mortar shops is the significantly lower upfront investments needed to open a new location, reflected by lower costs of real estate and personnel (ie. no servers, hosts, or bartenders), lower (and almost organic) customer acquisition costs, and larger economies of scale + scope.

- Better personalization (being direct to consumer)

- These startups can leverage data analytics to define respective target segments and create seasonal and limited-edition menu items for specific neighborhoods by looking at real-time consumption behavior.

- Better geolocation prediction

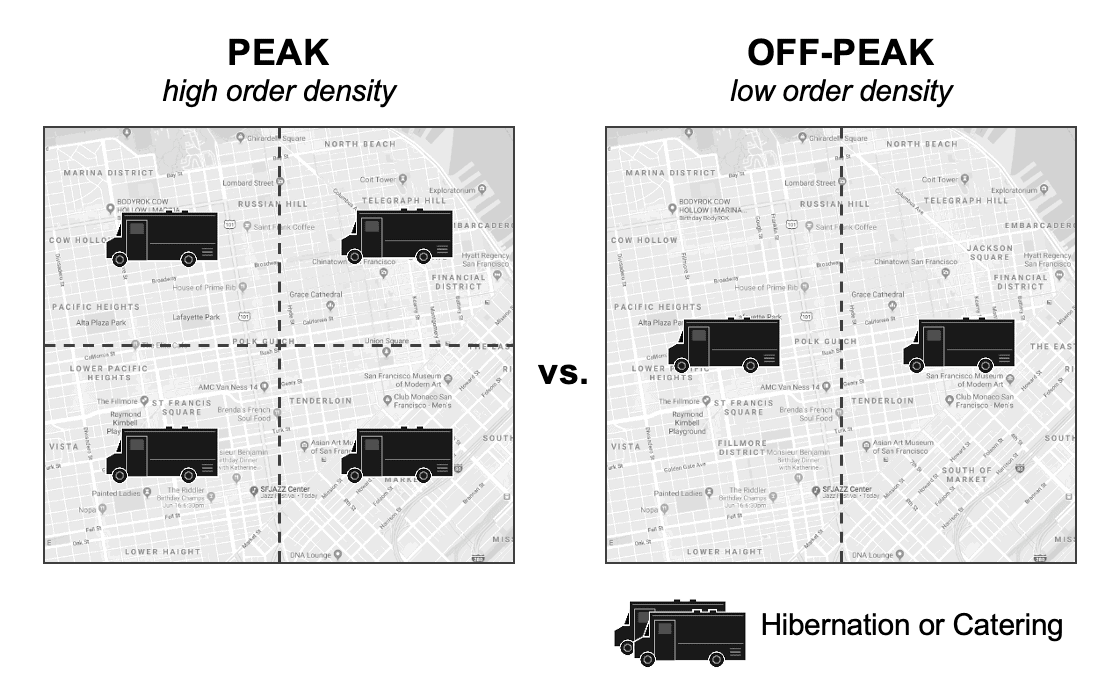

- Dynamic geo-positioning optimizes truck positions by day or day-part to capitalize on high order volume and control delivery times.

- As a result, this also optimizes labor utilization — trucks can move in and out of service based on profitability.

What will the future of food on-the-go look like?

As operators navigate cost pressures like labor, saving on occupancy rates — which can take up to 60% of a restaurant’s gross sales — can ease a significant burden on a low-margin business. While traditional restaurants can risk around $800,000 to test new menu items, if a menu fails at a virtual restaurant, it costs about $25,000. This is where a new wave of D2C virtual kitchens comes in.

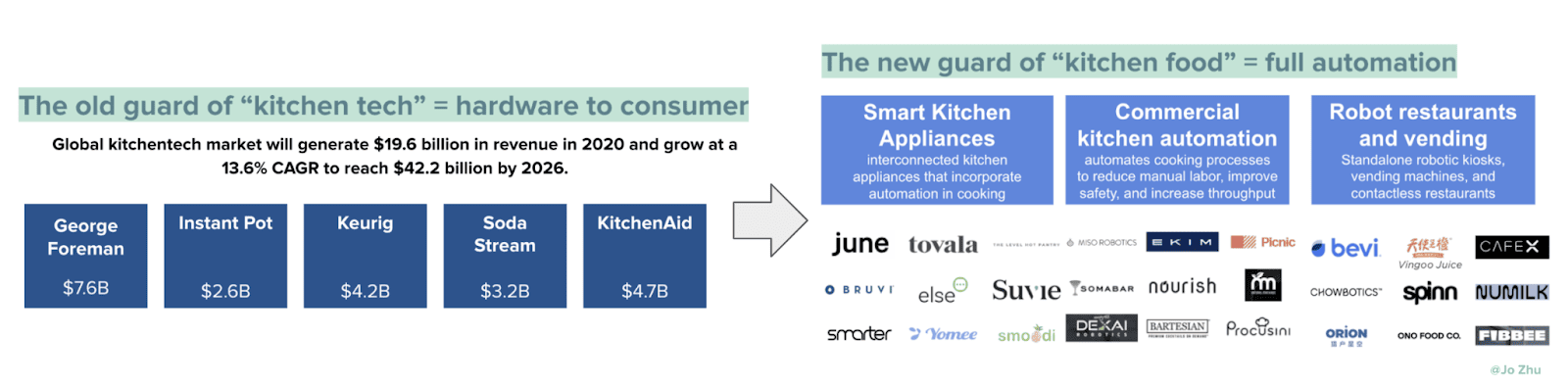

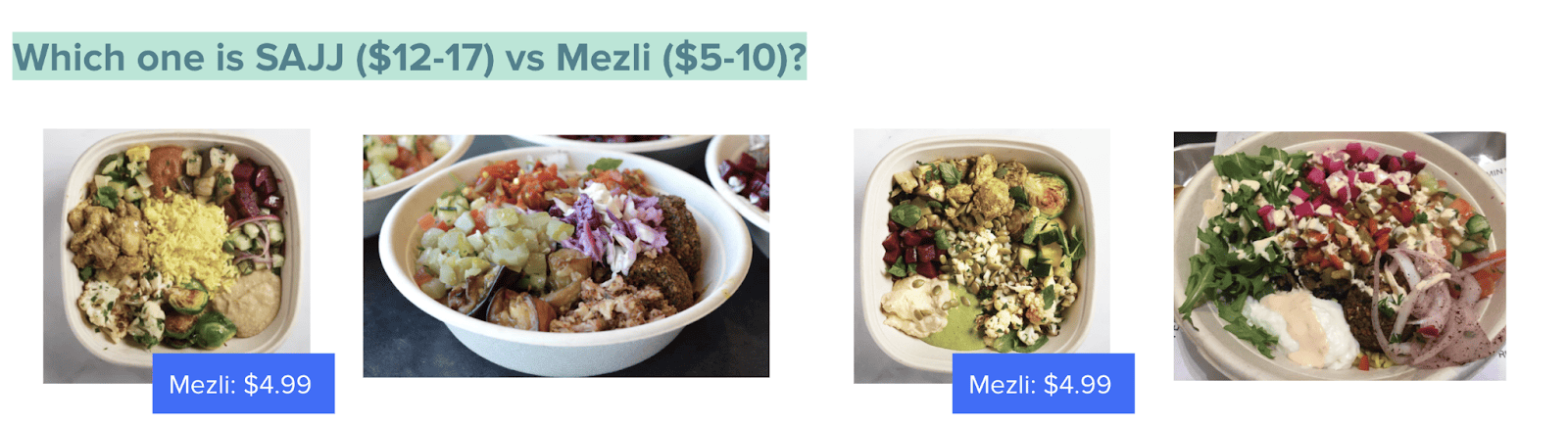

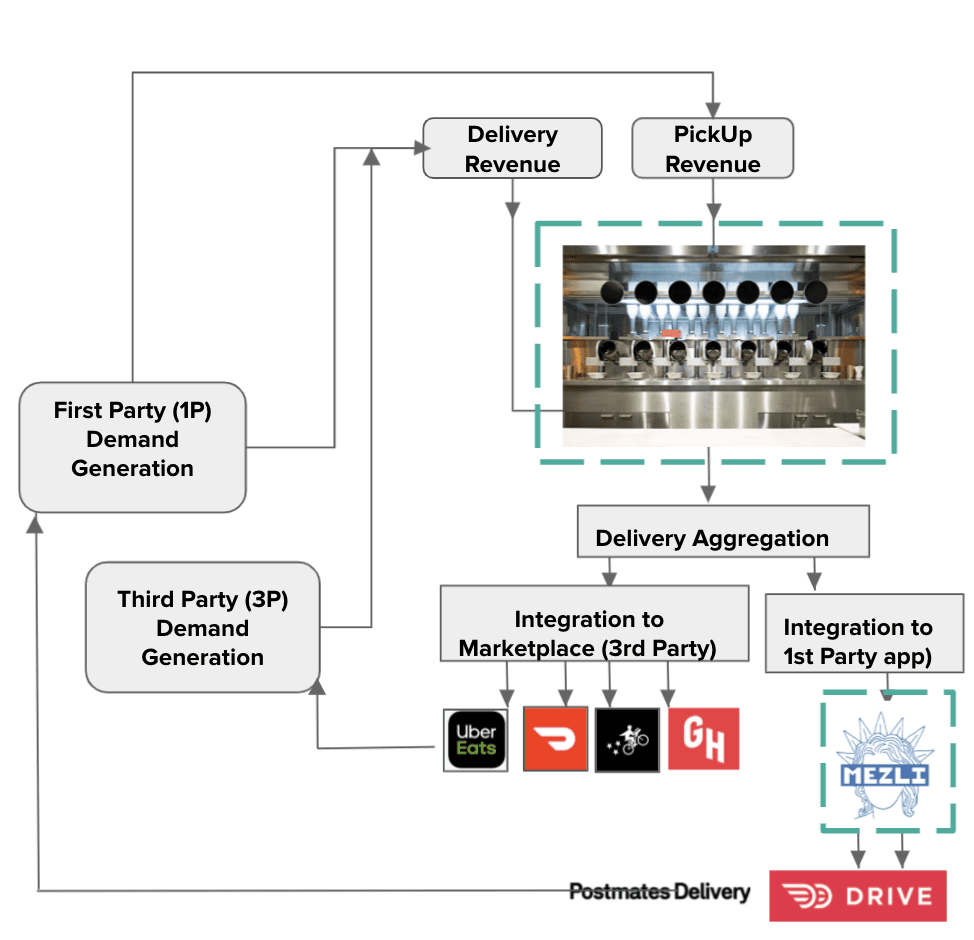

Kitchen automation is driven by an ongoing effort to reduce labor costs at restaurants while managing employee churn reduction. These challenges can drag significantly on margins. For the founders of Mezli, Mechanical Engineering grad students at Stanford, they didn’t have enough time to cook every meal, but also couldn’t afford to spend $15 or more at Sweetgreen and Mendocino Farms. It turns out that a lot of that high price point comes down to costs that are passed down to customers. Mezli’s differentiation is realizing that reducing the cost of building and operating a restaurant could unlock much cheaper great-quality meals and bump ROI by quite a bit!

In a world where the restaurateur constrained themselves to bowl-style meals (grain bowls, salads, soups, curries, etc.), much of the existing automation equipment that is off-the-shelf can be put in a shipping container and integrated with custom hardware to make an autonomous restaurant-in-a-box. The hardest parts of this will be self-cleaning as well as nimble dispensing technology – putting ingredients in a bowl reliably is not trivial – but Mezli has solved this in their most recent “auto-kitchen” patent.

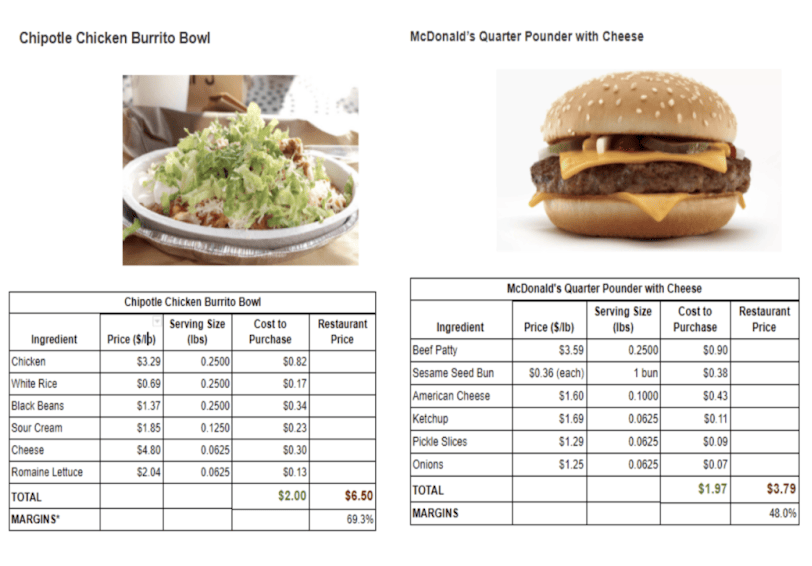

Like most restaurant chains, they do the bulk of their prep in a central kitchen (cutting up vegetables, seasoning their meats) and then the auto-kitchen itself uses a variety of heating and finishing steps (e.g. applying sauces and dry toppings) to make bowls to-order. Unlike some food automation companies, Mezli is focused on creating a fully automated “restaurant in a vending machine” rather than human-in-the-loop partial automation. In reality, less than 25% of the pricepoint on food is the raw ingredients themselves – the rest is labor, CapEx, and margin buffer:

Mezli’s end goal is to get their tech to work reliably enough to not need a human to monitor it. This would give Mezli food safety advantages because there’s less room for human error, and they could adopt procedures such as bathing the insides of their bowls with high-intensity UV light that kills germs (which would not be very employee-friendly!) With the pandemic accelerating the interest in automated kitchens, there have been many recent activities in the space – a few months ago, Spyce was acquired by Sweetgreen, and earlier in H1 2021, DoorDash acquired Chowbotics. The excitement in investments in this space makes sense as the restaurant industry is deemed essential amid global shutdowns, but finding kitchen staff proved a problem for many, especially early on when questions remained around COVID’s transmission.

In the near term, there will be continued investment in robotics and automation technologies that promise to reduce reliance on manual labor while improving product consistency and personalization. Food robotics, autonomous delivery, fresh vending concepts, and other novel technologies can reduce the cost of food production and distribution while also ensuring food safety. Robotics-as-a-Service (RaaS) sales models will help make advanced technologies more accessible for restaurants with limited investment capital. You can also explore part 1 of our future of food blog series and stay tuned for part 3!

For founders creating companies in the food tech space, we know we would love to chat! Feel free to drop me an email at jozhu@stanford.edu or Kathryn Weinmann at Norwest (kfw@nvp.com).